The Hidden Costs of Legacy Supply Chains in China: Why Cutting COGS Isn’t Enough

The Illusion of Cheap China

Doing business in China is not cheap, and it has not been cheap for some time. Long before tariffs became an existential concern for executives and boards, China has slowly but surely become an increasingly expensive market for foreign companies employing sourcing offices or knowledge workers. Yet, many companies have failed to take notice, and few are taking the transformative steps needed to maximize profitability in the region.

Over the last fifteen years, minimum wages in China have increased 170%, international freight from China to the US has roughly doubled in real terms, and key inputs from energy to raw materials continue to rise faster in China than in the US.

Beyond these economic measures, life expectancy and literacy rates in China have risen to nearly match the US, and incidence of extreme poverty is far less common in China than much of the developed world.

China isn’t a low-cost market anymore yet many supply chains still operate as if it is.

So does this mean China is no longer the factory of the world? It’s complicated, and rather than make proclamations on the end of Chinese manufacturing dominance, businesses would be better suited to start viewing China with a new lens. A lens that acknowledges that China can continue to play a vital role in manufacturing but is now a developed market, a macro-concession the Chinese themselves publicly acknowledged as they relinquished their “developing country status” with the WTO. With this transition, foreign companies must now seek to adopt a new management approach, one that focuses on efficiency if they are to successfully reduce supply chain costs.

And yet while 85% of executives surveyed by Boston Consulting Group have cited a desire to reduce supply chain costs, most companies attempting to do so in China, fail to address the root cause of rising expenses.

Today many companies still conduct business in China with a mercantilist mindset revolving around finding the lowest COGs and squeezing suppliers on tariff concessions, payment terms, and general performance. These companies to their credit, have been largely successful employing this playbook over the last two decades, but great organizations are recognizing that China is now a mature market which demands efficiency not opportunism, and that a fundamentally different approach to cost reductions is needed.

These companies are asking how can we operate smarter?

Why Most Cost Reduction Efforts Fail to Provide Lasting Benefits

Before we explore what smarter means, let’s look at how most companies approach supply chain cost reductions. To begin, companies often only take a critical look at supply chain expenses after a company is in crisis, a macro shock, or on an arbitrary set time interval measured in years not months.

When the time comes to trim supply chains costs, most look to negotiate lower prices with existing suppliers or re-source SKUs with new manufacturers with the goal of reducing their COGs.

Beyond supplier level negotiations, supply chain professionals then turn their attention towards negotiating freight terms, optimizing shipping routes, and for the ambitious, explore inventory policies which could reduce their working capital requirements.

Then, depending on available resources, companies may explore SKU or supplier rationalization to eliminate unprofitable products and achieve economies of scale, and lastly some will seek to implement lean improvements at the production or process level, even outsourcing warehousing or fulfillment to 3PL’s.

Individually, these strategies offer a nominal pathway to reduce supply chain costs and improve margins though the payoff, effort, time to implement, and sustainability around those potential cost savings varies greatly.

Most rising costs in China are not supplier-driven. They’re structural and internal.

In aggregate, all of these cost saving levers are valid and provide a pathway to margin improvement, but even in their totality, there are two issues. The first is that great companies evaluate supply chain costs on a regular basis and employ these very same strategies and tactics; meaning companies who use these same approaches every few years are not gaining a competitive advantage, but rather, closing a gap in race they are most likely already losing.

The second, is these approaches do not fundamentally address the root cause of rising costs in China which usually are not supplier related, but idiosyncratic and tied to one’s own supply chain organization.

The Hidden Cost of Legacy Supply Chain Organizations

So where then should executives direct their attention when looking to fundamentally reduce supply chain expenses if supplier and logistics negotiations are insufficient?

In acknowledging that China has become a developed market and that efficiency is required, companies must seek to understand what it costs to manage their supply chain from a systems perspective. This then becomes a question of how to operate smarter.

To help answer this question, companies can use a People, Process, Visibility, and Alignment framework. Essentially, this approach seeks to answer four key questions:

-

Do I have the right foreign staff to support my supply chain in the future?

-

Do we employ standard operating procedures which can deliver repeatable outcomes?

-

Do we have sufficient visibility across supply chain operations to make informed decisions?

-

Are suppliers and foreign staff aligned with our broader corporate goals?

In exploring these questions even at a 40,000ft view, many executives quickly realize that their foreign teams are bloated after decades of throwing cheap bodies at problems in lieu of addressing core issues; that supply chain procedures are incomplete or ad hoc, that supply chain data is incomplete, inaccurate, outdated, or not in a usable structure, and lastly, that suppliers and foreign staff are not aligned with broader strategic goals.

In turn, companies unknowingly or at least not intentionally have created an environment which leads to higher staffing costs, recurring issues which strain valuable domestic bandwidth, and can foster a culture of perpetual firefighting. Perhaps worst of all, these companies also experience reduced staff and supplier accountability, making it difficult to implement constructive improvements even when the opportunity presents itself.

These shortcomings historically have been classified as “the cost of doing business in China,” but this is no longer true.

These shortcomings historically have been classified as “the cost of doing business in China,” but this is no longer true. Today these operational and strategic gaps are not a byproduct of a developing country looking to find their footing on the global stage, instead these are symptoms of a “set it and forget it” mindset which plagues too many businesses large and small.

Our firm still sees this mindset when probing businesses as to why certain processes are used even though they have been clearly delivering sub-optimal results in some cases for years. Responses all too often are, “because that’s how we have always done it.” For companies looking to maximize efficiency in China one must recognize that how you built your supply chain in the region should be vastly different from how you manage your supply chain.

Ultimately many executives come to the conclusion that they need to implement supply chain improvements, perhaps even radical improvements; the issue then becomes how to scope and execute these transformations as most professionals have little prior experience restructuring a supply chain in Asia which to draw upon.

How Leading Companies Are Restructuring Their Global Footprint

To help guide those looking to transform their supply chain and sourcing organization in China, we can start by analyzing companies who have successfully reduced supply chain costs on a structural level.

These businesses which operate in over a dozen different industries and range from SME’s to publicly traded companies, have consistently completed three stages of a transformation process which any company can adopt.

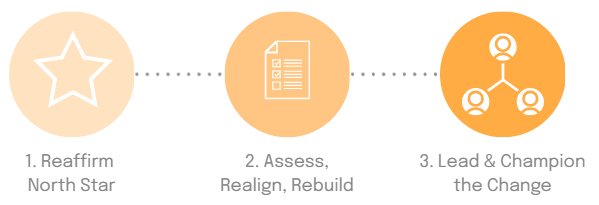

Transformation Stages

- Reaffirm North Star: What outcomes are we aiming to achieve?

- Assess, Realign, Rebuild: What must change to achieve them?

- Lead & Champion Change: How do we achieve buy-in and embed new ways of working across teams?

The first stage starts by revisiting or reaffirming a company’s broader objective and strategy. While most companies change corporate priorities throughout the course of time, few adjust their foreign teams, which creates meaningful gaps between corporate goals and capabilities on-the-ground. Through the process of reaffirming a company’s broader mission, executives can more easily create a North Star around the value their supply chain and foreign staff need to provide and communicate this vision with key stakeholders.

With a clear North Star, executives can then critically and objectively assess their foreign team’s roles, responsibilities, and performance in juxtaposition with broader corporate needs. In doing so, skill, process, and alignment gaps will begin to emerge. Closing these gaps is what unlocks structural cost savings.

As you complete this exercise be forewarned, those who approach this assessment with clear eyes often conclude that their teams in China do not provide significant strategic value, or at least, significantly less strategic value than they did ten or fifteen years ago. Importantly, this conclusion in of itself is not immediately an existential problem, it is only the failure to identify these gaps and adjust accordingly which can prove costly over time.

One common example of declining strategic value can be seen in a tenured staff member in China who was initially hired because they were bilingual, were personable and trustworthy, or had a strong relationship with a key supplier.

These individuals were typically early hires on a foreign team and have built close relationships with suppliers and domestic staff throughout the years. Since that time, however, many of these individuals have also ascended to managerial roles overseeing larger teams. In turn, executives looking to improve supply chain performance and reduce costs must ask themselves, “does this individual have the skills needed to manage people and drive process improvements?”

Today, the skills needed in China are vastly different than those which were required in decades passed. As China has matured, more suppliers have come to speak English, new vendors are easily identified, and even traveling from the US to China is hardly a chore. In turn, foreign teams today need to be able to Identify-Communicate-Solve-and Anticipate problems.

No longer can foreign staff be merely conduits of information from suppliers to domestic supply chain professionals, but rather they themselves must be capable of efficiently managing foreign operations.

Today, the skills needed in China are vastly different than those which were required in decades passed.

In completing a supply chain assessment, executives are often faced with two options:

- Alter and reshape existing team structure, upskill staff members, and implement new processes

- Retain core-competencies within existing foreign teams and outsource functions which can be more efficiently managed by a third party

The former is often the first stop on a company’s transformation journey, as it should be. Improving a group of individuals that you know, and trust is generally a low-risk proposition. The results around these internal improvement initiatives though can be mixed, with most companies capturing only marginal cost saving, some of which are not sustained as companies slide back into poor habits.

For those who have significantly underperforming teams, require substantial restructuring, or desire a more radical supply chain transformation, outsourcing and leveraging external expertise often delivers the greatest value.

Since the rise of e-commerce in the 2000’s many businesses have already turned to outsourced warehousing and fulfillment to reduce logistics costs. Moving further upstream, third party quality control and auditing in Asia has become commonplace, and now businesses are adopting outsourced supply chain management strategies as they work to minimize overall costs.

This asset-light approach to supply chain management has shown to deliver far greater cost savings than incremental improvements with existing teams while at the same time increasing operational flexibility.

Many organizations realize they can’t fix entrenched inefficiencies with the same teams that created them.

However, whichever approach a company pursues, the third and final component of a successful transformation is direct oversight from the C-Suite during scoping, execution, and evaluation of any improvements. While supply chain practitioners ultimately are responsible for completing the tasks associated with a transformation road map, executives must still resist the urge to delegate and disengage until victory can be claimed.

By leading from above, executives can more easily achieve buy-in among the rank and file, establish much needed accountability, and signal that difficult decisions around team size or business processes are tied to serving the broader corporate mission. This engagement by the C-suite differentiates a true strategic cost-saving initiative, from any previous incremental efforts which may have failed to fully deliver on their promise.

And as companies soon discover, a supply chain transformation in China can be often a precursor to broader cultural change throughout an entire organization, which is yet another reason why transformative steps need to be visibly championed by the C-suite.

Achieving Reduced Costs and Unlocking New Possibilities

When assessing the benefits associated with reorienting a legacy supply chain in China towards efficiency, companies typically see three key areas of improvement. The first is obviously around the reduction of management costs, often approaching 30%. These savings are tied to smaller staff sizes, lower operating costs, and in many cases downsizing or eliminating fixed overhead.

Beyond these structural cost savings, companies also frequently capture further savings through improved performance. While harder to quantify, our firm has observed that companies with lean foreign teams, strong processes, and a high degree of supplier alignment, are better able to address potential issues before they compound into larger problems. In these instances, companies are able to achieve improved visibility which results in lower logistics costs and better quality performance.

Structural changes can reduce management costs by up to 30%.

Lastly, while most companies initiate a supply chain transformation with the goal of reducing supply chain costs, many soon come to realize that underperforming legacy sourcing organizations may have had a meaningfully negative impact on a business’s internal culture and subsequent performance. Perpetual firefighting, finger pointing, and inconsistent flow of information all wreak havoc on domestic supply chain professionals.

These domestics teams are often forced to implement inefficient workarounds and delay new strategic initiatives as they toil to simply keep their supply chain moving forward. Companies that successfully create leaner more efficient supply chains in China quickly see that their domestic teams make better decisions, face fewer bandwidth constraints, and finally have the time to pursue new opportunities.

In the end, a company’s supply chain organization in China should not be a source of ballooning costs and troubleshooting. Instead, one’s supply chain organization should be well aligned with a company’s business objectives and efficiently execute operations as outlined by supply chain executives.

Companies who recognize that their legacy supply chain organizations and management approaches in China are outdated and take steps towards increasing efficiency soon find themselves with higher performing, capital efficient, and more flexible supply chains- leading executives to ask themselves, “Why did we take so long to pivot in China?”